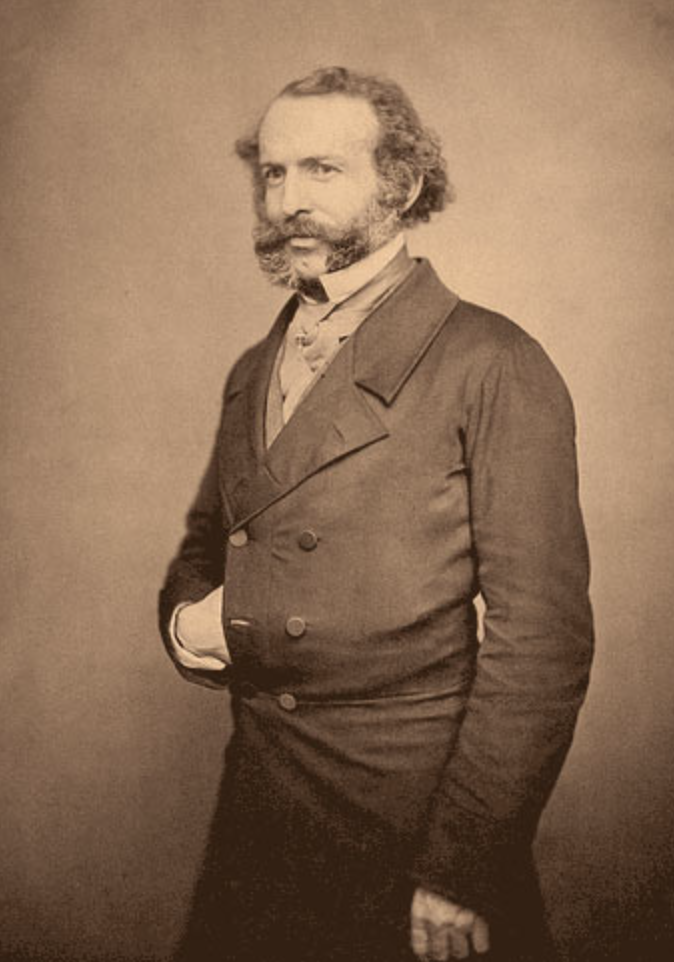

39. John Rae - Arctic explorer extraordinary

By far the most impressive European explorer of the Arctic in the 19th century was Dr John Rae (1813-1893). An employee of the Hudson’s Bay Company, born in the Orkney Islands, he was the first to realise the vital importance of adopting the skills of native peoples.

Rae led four expeditions to the Canadian Arctic in the 1840s and 50s, and surveyed nearly 2,500 km of previously unmapped coast. He was a man of extraordinary physical toughness - on one occasion he covered 170 km in two days in snowshoes - and an expert hunter and boatman. He also employed the tools of celestial navigation (including the use of lunar distance observations for determining longitude) to good effect.

But what really distinguishes Rae is the extraordinary efficiency of his expeditions.

Unlike every other Arctic explorer of the period, Rae travelled very light, with small teams of European and native companions. They lived largely off the land, maintained good relations with the local Inuit, adopted their style of clothing and learned from them how to build well-insulated ‘ice houses’ (igloos).

Rae was the first to prove that Europeans could survive the Arctic winter on land (rather than in well-provisioned and heated ships). More remarkable still, he only ever lost one man - who drowned accidentally in fierce rapids on the Coppermine River.

Though Rae won the prestigious Founder’s Gold Medal from the Royal Geographical Society and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, he was denied the public recognition that was his due. In fact it was only in 2014 that a memorial to him was unveiled in Westminster Abbey.

Why? Largely because he told an uncomfortable truth.

Franklin had sailed from Stromness in Orkney in May 1845 with two Royal Navy ships: HMS Terror and HMS Erebus in the hope of finding the ‘last link’ in the fabled North West Passage. When nothing had been heard from him after two years, people began to worry - with good reason. The expedition cost Franklin’s own life as well as those of everyone who sailed with him - 128 men.

Rae was the first to find evidence of what had happened to Franklin’s men. In 1854 he met some Inuit hunters who reported that a large number of Europeans had been seen either dead or dying four years earlier. Later other Inuit brought him physical evidence of the Franklin expedition, including a silver plate, as well as knives and forks with initials.

Rae interviewed the Inuit closely and gathered more details, including the sad but unsurprising news that the starving sailors had resorted to eating the flesh of their dead comrades. Their supplies of tinned food had run out and they lacked the skills to live off the land. Scurvy and other illnesses (possibly including lead poisoning caused by faulty canning) as well as poor clothing and equipment added to their woes.

Rae returned to London as quickly as possible and reported to the Admiralty in October 1854. Unfortunately for him, his private account of the crew’s cannibalism quickly reached The Times, which did not hesitate to publish this sensational news.

Although anyone who knew anything about survival could well understand what had happened, Victorian public opinion was not ready to accept that British sailors could break such a sacred taboo. And Lady Franklin, a determined and well-connected figure, was outraged at the suggestion that her husband might have condoned acts of cannibalism. (In fact, it later turned out, he couldn’t have done because he died months before his men began to starve.) If such ‘barbarities’ had indeed occurred, they must surely have been the work of ‘Esquimaux’ savages. The novelist and journalist Charles Dickens sprang to her support publishing an article that poured scorn on Rae’s account of what had happened.

Rae was appalled and especially indignant on behalf of the Inuit people whom he so much respected. But there was little he could do to turn things round. Lady Franklin never forgave him and neither did the rest of the British Establishment. Nevertheless, Rae was grudgingly given the £10,000 reward that was due to anyone who discovered the fate of the Franklin expedition. This he shared with the men who had accompanied him - including the Inuit.

When the remains of some of the dead crew were later discovered, it became clear that the Inuit account of cannibalism among them was indeed accurate. Within the last ten years the wrecks of Terror and Erebus have been discovered, remarkably well-preserved beneath the Arctic waters. Continuing archaeological enquiries may yet shed further light on Franklin’s disastrous expedition.

Thanks to Lady Franklin’s lobbying, her husband was publicly credited with the ‘discovery’ of the North West Passage and many still believe that he did indeed achieve this feat. But while it’s true that his two ships were heading in the right direction when they were beset in the ice, they certainly did not finish the job, and anyway by then Franklin himself had already died.

A futile debate still rages about who should properly be honoured for ‘discovering’ the North West Passage. Futile because there are actually several such passages and much depends on what counts as ‘discovery’. In truth it was a gradual process that lasted many years - arguably several centuries - to which many different people (including Rae) contributed.

The first man to sail from the Atlantic to the Pacific via the Arctic was the Norwegian, Roald Amundsen (1872-1928), who did so in the small ship Gjøa in 1903-1906. Like Rae before him, Amundsen learned much from the Inuit while overwintering in the Arctic and he made good use of this experience in planning the first successful expedition to the South Pole in 1911. He paid tribute to Rae for discovering the narrow and relatively ice-free strait (named after Rae) on which his transit of the North West Passage crucially depended. Today, thanks to global warming, it is quite easy to sail through - small sailing yachts have even done so.

Roald Amundsen

Let me end with a quotation that reveals something of Rae’s resolute character - and his knack for understatement. It comes from the account of his first Arctic expedition:

‘The 9th [of January 1847] was a more disagreeable day than any we had yet had. A storm from the north with thick snow-drift, and a temperature of 72° below the freezing point, made it feel bitterly cold. Fortunately we had some days before made a house for our dogs, else they must have inevitably been frozen to death. Such was the force of the gale for two days that both observatories were completely demolished, and wherever the snow banks projected in the slightest degree above the surrounding level, they were worn away by the friction of the snow-drift as if cut with a knife.

‘The thermometer indoors varied from 29° to 40° below the freezing point; which would not have been unpleasant where there was a fire to warm the hands and feet, or even room to move about; but where there was neither the one nor the other, some few degrees more heat would have been preferable.

‘As we could not go for water we were forced to thaw snow, and take only one meal each day. My waistcoat after a week's wearing became so stiff from the condensation and freezing of my breath upon it, that I had much trouble to get it buttoned.’

Hats off!

Memorial to John Rae in St Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall (artist unidentified)